前言

这章讲的是文件 IO,其中有几个非常重要的概念:

- File Desriptors,文件描述符

- current file offset,当前文件偏移量

- File Sharing Data Structure,文件共享数据模型

- file descriptor flags ,文件描述位

- file status flags ,文件状态位

File Descriptors

- 对内核来说,所有 打开的文件 都使用 file descriptor 引用。

- 文件描述符是一个非负整数。当我们打开一个存在的文件或者创建一个新文件,内核返回一个文件描述符给进程。

- 当我们想要读或者写一个文件,我们通过文件描述符来确定这个文件,文件描述符是被 open 或者 creat 返回的,然后作为 read 或者 write 的一个参数。

文件描述符都使用尽可能小的非负整数,File descriptors range from 0 through OPEN_MAX−1.

有三个 magic number,0 代表 STDIN_FILENO,1 代表 STDOUT_FILENO,2 代表 STDERR_FILENO。虽然这已经是 POSIX.1 所定义的标准,但为了程序的可读性,还是不建议直接写数字。这三个常量定义在<unistd.h>中。

open and openat Functions

A file is opened or created by calling either the open function or the openat function.

1 |

|

最后一个参数是...,这是 ISO C 定义剩下的多个参数的方式。对这些函数来说,只有当新文件被创建时,最后一个参数才被使用,后面我们会讲。在这个原型中我们把这个参数写作一个注释。

path 这个参数是要打开或者要创建的文件的名字。这个函数有多种操作,定在在 oflag 参数里。这个参数由下列一个或者多个定义在<fcntl.h>头文件中的常量通过 或(一种逻辑操作) 操作构成:

O_RDONLY Open for reading only

O_WRONLY Open for writing only

O_RDWR Open for reading and writing

Most implementations define O_RDONLY as 0, O_WRONLY as 1, and O_RDWR as 2, for compatibility with older programs. 为了兼容老程序,许多实现定义 O_RDONLY as 0, O_WRONLY as 1, and O_RDWR as 2。

O_EXEC Open for execute only

O_SEARCH Open for search only(applies to directories)

The purpose of the O_SEARCH constant is to evaluate search permissions at the time a directory is opened. Further operations using the directory’s file descriptor will not reevaluate permission to search the directory. None of the versions of the operating systems covered in this book support O_SEARCH yet.

One and only one of the previous five constants must be specified. The following constants are optional:

上面的五个常量有且只有一个必须被明确。接下来的是可选常量:

O_APPEND Append to the end of file on each write. We describe this option in detail in Section 3.11.

O_CLOEXEC Set the FD_CLOEXEC file descriptor flag. We discuss file descriptor flags in Section 3.14.

O_CREAT Create the file if it doesn’t exist. This option requires a third argument to the open function (a fourth argument to the openat function) — the mode, which specifies the access permission bits of the new file. (When we describe a file’s access permission bits in Section 4.5, we’ll see how to specify the mode and how it can be modified by the umask value of a process.) 创建一个文件,如果不存在。这个操作需要 open 函数的第三个参数(openat 函数的第四个参数)— mode,它明确了这个新文件的访问权限位。(当我们在第 4.5 章节讨论文件的访问权限位,我们将看到如何明确 mode,以及它如何修改进程的 umask 值。)

O_DIRECTORY Generate an error if path doesn’t refer to a directory.

O_EXCL Generate an error if O_CREAT is also specified and the file already exists. This test for whether the file already exists and the creation of the file if it doesn’t exist is an atomic operation. We describe atomic operations in more detail in Section 3.11. 如果 O_CREAT 被使用了且文件已经存在就会生成一个错误。这个常量的作用是检测文件是否存在如果文件不存在就创建,这是一个原子操作。我们将在第 3.11 章节讨论更多原子操作的细节。

O_NOCTTY If path refers to a terminal device, do not allocate the device as the controlling terminal for this process. We talk about controlling terminals in Section 9.6. 如果这个路径指向的是终端设备,则不将这个设备分配为此进程的控制终端。

O_NONBLOCK If path refers to a FIFO, a block special file, or a character special file, this option sets the nonblocking mode for both the opening of the file and subsequent I/O. We describe this mode in Section 14.2. 如果 path 指向 FIFO(先进先出),一个块特殊文件,一个字符特殊文件,这个选项设置了非阻塞模式为本次的打开操作和后续的 I/O 操作。

In earlier releases of System V, the O_NDELAY (no delay) flag was introduced. This option is similar to the O_NONBLOCK (nonblocking) option, but an ambiguity was introduced in the return value from a read operation. The no-delay option causes a read operation to return 0 if there is no data to be read from a pipe, FIFO, or device, but this conflicts with a return value of 0, indicating an end of file. SVR4-based systems still support the no-delay option, with the old semantics, but new applications should use the nonblocking option instead. 在早期的 System V,有一个 O_NDELAY(no delay)符号。这个符号和 O_NONBLOCK(nonblocking)选项相似,但他的读操作返回值具有二义性。如果管道,先进先出,或者设备没有数据可读,no-delay 选项就会造成 read 操作返回 0,这与 end of file 造成的返回值 0 冲突了。虽然基于 SVR4 的系统还支持这个 no-delay 选项,但新的应用应该使用 nonblocking 选项。

O_SYNC Have each write wait for physical I/O to complete, including I/O necessary to update file attributes modified as a result of the write. We use this option in Section 3.14. 使每次 write 都等物理 I/O 完成,包括更新文件属性所需要的 I/O。

O_TTY_INIT When opening a terminal device that is not already open, set the nonstandard termios parameters to values that result in behavior that conforms to the Single UNIX Specification. We discuss the termios structure when we discuss terminal I/O in Chapter 18. 当打开一个新的终端设备的时候,设置非标准参数 termios。

The following two flags are also optional. They are part of the synchronized input and output option of the Single UNIX Specification (and thus POSIX.1).

O_DSYNC Have each write wait for physical I/O to complete, but don’t wait for file attributes to be updated if they don’t affect the ability to read the data just written. 让所有 write 都等待物理 I/O 完成,但是不用等文件属性更新,如果不影响刚刚写完的数据的读操作的话。

O_RSYNC Have each read operation on the file descriptor wait until any pending writes for the same portion of the file are complete. 使每个使用文件描述符的的读操作等待,直到对文件的同一部分的所有写操作完成。

Solaris 10 supports all three synchronization flags. Historically, FreeBSD (and thus Mac OS X) have used the O_FSYNC flag, which has the same behavior as O_SYNC. Because the two flags are equivalent, they define the flags to have the same value. FreeBSD 8.0 doesn’t support the O_DSYNC or O_RSYNC flags. Mac OS X doesn’t support the O_RSYNC flag, but defines the O_DSYNC flag, treating it the same as the O_SYNC flag. Linux 3.2.0 supports the O_DSYNC flag, but treats the O_RSYNC flag the same as O_SYNC.

The file descriptor returned by open and openat is guaranteed to be the lowest- numbered unused descriptor. This fact is used by some applications to open a new file on standard input, standard output, or standard error. For example, an application might close standard output—normally, file descriptor 1—and then open another file, knowing that it will be opened on file descriptor 1. We’ll see a better way to guarantee that a file is open on a given descriptor in Section 3.12, when we explore the dup2 function.

The fd parameter distinguishes the openat function from the open function. There are three possibilities:

The path parameter specifies an absolute pathname. In this case, the fd parameter is ignored and the openat function behaves like the open function.

The path parameter specifies a relative pathname and the fd parameter is a file descriptor that specifies the starting location in the file system where the relative pathname is to be evaluated. The fd parameter is obtained by opening the directory where the relative pathname is to be evaluated.

The path parameter specifies a relative pathname and the fd parameter has the special value AT_FDCWD. In this case, the pathname is evaluated starting in the current working directory and the openat function behaves like the open function.

The openat function is one of a class of functions added to the latest version of POSIX.1 to address two problems. First, it gives threads a way to use relative pathnames to open files in directories other than the current working directory. As we’ll see in Chapter 11, all threads in the same process share the same current working directory, so this makes it difficult for multiple threads in the same process to work in different directories at the same time. Second, it provides a way to avoid time-of-check- to-time-of-use (TOCTTOU) errors. openat 函数是在最后一个版本的 POSIX.1 加入的,为了解决两个问题。首先,它给线程以相对路径而非当前路径。我们将在第 11 章看到,在同一进程中的所有线程共享同一个当前目录,所以要让同一进程中的多线程同时在不同的目录工作是非常困难的。第二,它提供了避免 time-of-check-to-time-of-use(TOCTTOU) 错误。

The basic idea behind TOCTTOU errors is that a program is vulnerable if it makes two file-based function calls where the second call depends on the results of the first call. Because the two calls are not atomic, the file can change between the two calls, thereby invalidating the results of the first call, leading to a program error. TOCTTOU errors in the file system namespace generally deal with attempts to subvert file system permissions by tricking a privileged program into either reducing permissions on a privileged file or modifying a privileged file to open up a security hole. Wei and Pu [2005] discuss TOCTTOU weaknesses in the UNIX file system interface. TOCTTOU 错误的意思是,一个调用横叉一脚影响了另一个调用,本来另一个调用应该是一个原子操作。

Filename and Pathname Truncation

What happens if NAME_MAX is 14 and we try to create a new file in the current directory with a filename containing 15 characters? Traditionally, early releases of System V, such as SVR2, allowed this to happen, silently truncating the filename beyond the 14th character. BSD-derived systems, in contrast, returned an error status, with errno set to ENAMETOOLONG. Silently truncating the filename presents a problem that affects more than simply the creation of new files. If NAME_MAX is 14 and a file exists whose name is exactly 14 characters, any function that accepts a pathname argument, such as open or stat, has no way to determine what the original name of the file was, as the original name might have been truncated. 如果 NAME_MAX 是 14 怎么办?传统上,早期的 System V 系统,允许这发生,静默的将文件名截断成 14 字符。相反的,BSD 派生的系统,返回一个错误状态,并把 errno 设置成 ENAMETOOLONG。静默的截断文件名呈现的问题不仅仅是创建了一个新文件。如果 NAME_MAX 是 14 且文件存在,且它的名字就是 14 字符,任何接收一个路径名作为参数的函数,比如 open 或者 stat,没办法判断文件原来的名字是什么,因为原始文件名可能已经被截断。

With POSIX.1, the constant _POSIX_NO_TRUNC determines whether long filenames and long components of pathnames are truncated or an error is returned. As we saw in Chapter 2, this value can vary based on the type of the file system, and we can use fpathconf or pathconf to query a directory to see which behavior is supported. 在 POSIX.1 标准里,常量 _POSIX_NO_TRUNC 决定长文件名和路径名中长的组件是否被截断或者是否返回一个错误。正如我们在第二章中看到的,这个值在文件系统中是非常基本的,我们可以使用 fpathconf 或 pathconf查询一个目录看看它支持哪种行为。

Whether an error is returned is largely historical. For example, SVR4-based systems do not generate an error for the traditional System V file system, S5. For the BSD-style file system (known as UFS), however, SVR4-based systems do generate an error. Figure 2.20 illustrates another example: Solaris will return an error for UFS, but not for PCFS, the DOS-compatible file system, as DOS silently truncates filenames that don’t fit in an 8.3 format. BSD-derived systems and Linux always return an error.

If _POSIX_NO_TRUNC is in effect, errno is set to ENAMETOOLONG, and an error status is returned if any filename component of the pathname exceeds NAME_MAX.

Most modern file systems support a maximum of 255 characters for filenames. Because filenames are usually shorter than this limit, this constraint tends to not present problems for most applications.

creat Function

A new file can also be created by calling the creat function.

1 |

|

Note that this function is equivalent to

1 | open(path, O_WRONLY | O_CREAT | O_TRUNC, mode); |

Historically, in early versions of the UNIX System, the second argument to open could be only 0, 1, or 2. There was no way to open a file that didn’t already exist. Therefore, a separate system call, creat, was needed to create new files. With the O_CREAT and O_TRUNC options now provided by open, a separate creat function is no longer needed. 这个函数诞生的原因是:历史上 open 函数的第二个参数只支持 0,1,2 这三个值,也就是读,写,读写。没办法打开一个不存在的文件。而现在有了 O_CREAT and O_TRUNC options,creat 函数也就没有存在的必要了。

We’ll show how to specify mode in Section 4.5 when we describe a file’s access permissions in detail.

One deficiency with creat is that the file is opened only for writing. Before the new version of open was provided, if we were creating a temporary file that we wanted to write and then read back, we had to call creat, close, and then open. A better way is to use the open function, as in

1 | open(path, O_RDWR | O_CREAT | O_TRUNC, mode); |

close Function

An open file is closed by calling the close function.

1 |

|

Closing a file also releases any record locks that the process may have on the file. We’ll discuss this point further in Section 14.3. 关闭一个文件同样会释放进程对该文件的所有锁。

When a process terminates, all of its open files are closed automatically by the kernel. Many programs take advantage of this fact and don’t explicitly close open files. See the program in Figure 1.4, for example. 当一个进程终止,所有它打开的文件都会被内核自动关闭。许多程序利用了这一点,不明确关闭文件。

lseek Function

Every open file has an associated “current file offset,” normally a non-negative integer that measures the number of bytes from the beginning of the file. (We describe some exceptions to the ‘‘non-negative’’ qualifier later in this section.) Read and write operations normally start at the current file offset and cause the offset to be incremented by the number of bytes read or written. By default, this offset is initialized to 0 when a file is opened, unless the O_APPEND option is specified. 每个打开的文件都与 "current file offset"关联,正常情况下它是一个非负整形数,表示从文件开始到目前位置的字节数。读和写操作都是从 current file offset 开始的,并且会让 offset 增加,随着读和写的进行。默认的,当文件被打开时,这个位移初始化时 0,除非指明了 O_APPEND 选项。

An open file’s offset can be set explicitly by calling lseek. 通过调用 lseek 函数,一个打开的文件的 offset 可以被设定。

1 |

|

The interpretation of the offset depends on the value of the whence argument.

- If whence is SEEK_SET, the file’s offset is set to offset bytes from the beginning of the file.

- If whence is SEEK_CUR, the file’s offset is set to its current value plus the offset. The offset can be positive or negative.

- If whence is SEEK_END, the file’s offset is set to the size of the file plus the offset. The offset can be positive or negative.

Because a successful call to lseek returns the new file offset, we can seek zero bytes from the current position to determine the current offset:

1 | off_t currpos; |

This technique can also be used to determine if a file is capable of seeking. If the file descriptor refers to a pipe, FIFO, or socket, lseek sets errno to ESPIPE and returns −1.

The three symbolic constants—SEEK_SET, SEEK_CUR, and SEEK_END—were introduced with System V. Prior to this, whence was specified as 0 (absolute), 1 (relative to the current offset), or 2 (relative to the end of file). Much software still exists with these numbers hard coded.

The character l in the name lseek means ‘‘long integer.’’ Before the introduction of the off_t data type, the offset argument and the return value were long integers. lseek was introduced with Version 7 when long integers were added to C. (Similar functionality was provided in Version 6 by the functions seek and tell.)

Example

The program in Figure 3.1 tests its standard input to see whether it is capable of seeking.

Figure 3.1 Test whether standard input is capable of seeking

1 |

|

Normally, a file’s current offset must be a non-negative integer. It is possible, however, that certain devices could allow negative offsets. But for regular files, the offset must be non-negative. Because negative offsets are possible, we should be careful to compare the return value from lseek as being equal to or not equal to −1, rather than testing whether it is less than 0.

The /dev/kmem device on FreeBSD for the Intel x86 processor supports negative offsets. Because the offset (off_t) is a signed data type (Figure 2.21), we lose a factor of 2 in the maximum file size. If off_t is a 32-bit integer, the maximum file size is $2^{31}$−1 bytes.

lseek only records the current file offset within the kernel — it does not cause any I/O to take place. This offset is then used by the next read or write operation.

The file’s offset can be greater than the file’s current size, in which case the next write to the file will extend the file. This is referred to as creating a hole in a file and is allowed. Any bytes in a file that have not been written are read back as 0. 文件偏移量可以大于文件的目前大小,在这种情况下下一次写文件将扩展文件。也就是说在文件中创建一个空洞是被允许的。在文件中任何没被写入的部分都将被读作 0。

A hole in a file isn’t required to have storage backing it on disk. Depending on the file system implementation, when you write after seeking past the end of a file, new disk blocks might be allocated to store the data, but there is no need to allocate disk blocks for the data between the old end of file and the location where you start writing. 文件中的空洞并不需要存储到磁盘上。根据文件系统的实现,当你在 end of file 之后写,为了存储数据新的磁盘空间可能会分配,但没有必要分配磁盘块给 end of file 和你开始写的地方之间的这些数据。

Example

The program shown in Figure 3.2 creates a file with a hole in it.

Figure 3.2 Create a file with a hole in it

1 |

|

read Function

Data is read from an open file with the read function.

1 | #include <unistd.h> |

Returns: numbers of bytes read, 0 if end of file, -1 on error

If the read is successful, the number of bytes read is returned. If the end of file is encountered, 0 is returned.

There are several cases in which the number of bytes actually read is less than the amount requested: 有以下几种情况,read 读取的字节会比指定的字节数少

- When reading from a regular file, if the end of file is reached before the requested number of bytes has been read. For example, if 30 bytes remain until the end of file and we try to read 100 bytes, read returns 30. The next time we call read, it will return 0 (end of file).

- When reading from a terminal device. Normally, up to one line is read at a time. (We’ll see how to change this default in Chapter 18.)

- When reading from a network. Buffering within the network may cause less than the requested amount to be returned.

- When reading from a pipe or FIFO. If the pipe contains fewer bytes than requested, read will return only what is available.

- When reading from a record-oriented device. Some record-oriented devices, such as magnetic tape, can return up to a single record at a time.

- When interrupted by a signal and a partial amount of data has already been read. We discuss this further in Section 10.5.

The read operation starts at the file’s current offset. Before a successful return, the offset is incremented by the number of bytes actually read. read 操作是从文件的当前偏移量开始的。在成功返回前,偏移量会随读取的字节增加。

POSIX.1 changed the prototype for this function in several ways. The classic definition is

1 | int read(int fd, char *buf, unsigned nbytes); |

- First, the second argument was changed from char _ to void _ to be consistent

with ISO C: the type void * is used for generic pointers. - Next, the return value was required to be a signed integer (ssize_t) to return a positive byte count, 0 (for end of file), or −1 (for an error).

- Finally, the third argument historically has been an unsigned integer, to allow a 16-bit implementation to read or write up to 65,534 bytes at a time. With the 1990 POSIX.1 standard, the primitive system data type ssize_t was introduced to provide the signed return value, and the unsigned size_t was used for the third argument. (Recall the SSIZE_MAX constant from Section 2.5.2.)

write Function

Data is written to an open file with the write function.

1 | #include <unistd.h> |

The return value is usually equal to the nbytes argument; otherwise, an error has occurred. A common cause for a write error is either filling up a disk or exceeding the file size limit for a given process (Section 7.11 and Exercise 10.11). 返回值一般会等于nbytes这个参数的大小,否则就是出错了。一般导致写错误的原因是磁盘满了或者超出给定进程的文件大小限制。

For a regular file, the write operation starts at the file’s current offset. If the O_APPEND option was specified when the file was opened, the file’s offset is set to the current end of file before each write operation. After a successful write, the file’s offset is incremented by the number of bytes actually written.

I/O Efficiency

The program in Figure 3.5 copies a file, using only the read and write functions.

Figure 3.5 Copy standard input to standard output

1 | #include "apue.h" |

The following caveats apply to this program.

- It reads from standard input and writes to standard output, assuming that these have been set up by the shell before this program is executed. Indeed, all normal UNIX system shells provide a way to open a file for reading on standard input and to create (or rewrite) a file on standard output. This prevents the program from having to open the input and output files, and allows the user to take advantage of the shell’s I/O redirection facilities.

- The program doesn’t close the input file or output file. Instead, the program uses the feature of the UNIX kernel that closes all open file descriptors in a process when that process terminates.

- This example works for both text files and binary files, since there is no difference between the two to the UNIX kernel.

One question we haven’t answered, however, is how we chose the BUFFSIZE value. Before answering that, let’s run the program using different values for BUFFSIZE. Figure 3.6 shows the results for reading a 516,581,760-byte file, using 20 different buffer sizes.

The file was read using the program shown in Figure 3.5, with standard output redirected to /dev/null. The file system used for this test was the Linux ext4 file system with 4,096-byte blocks. (The st_blksize value, which we describe in Section 4.12, is 4,096.) This accounts for the minimum in the system time occurring at the few timing measurements starting around a BUFFSIZE of 4,096. Increasing the buffer size beyond this limit has little positive effect.

Most file systems support some kind of read-ahead to improve performance. When sequential reads are detected, the system tries to read in more data than an application requests, assuming that the application will read it shortly. The effect of read-ahead can be seen in Figure 3.6, where the elapsed time for buffer sizes as small as 32 bytes is as good as the elapsed time for larger buffer sizes.

We’ll return to this timing example later in the text. In Section 3.14, we show the effect of synchronous writes; in Section 5.8, we compare these unbuffered I/O times with the standard I/O library.

Beware when trying to measure the performance of programs that read and write files. The operating system will try to cache the file incore, so if you measure the performance of the program repeatedly, the successive timings will likely be better than the first. This improvement occurs because the first run causes the file to be entered into the system’s cache, and successive runs access the file from the system’s cache instead of from the disk. (The term incore means in main memory. Back in the day, a computer’s main memory was built out of ferrite core. This is where the phrase ‘‘core dump’’ comes from: the main memory image of a program stored in a file on disk for diagnosis.)

In the tests reported in Figure 3.6, each run with a different buffer size was made using a different copy of the file so that the current run didn’t find the data in the cache from the previous run. The files are large enough that they all don’t remain in the cache (the test system was configured with 6 GB of RAM).

File Sharing

The UNIX System supports the sharing of open files among different processes. Before describing the dup function, we need to describe this sharing. To do this, we’ll examine the data structures used by the kernel for all I/O.

The following description is conceptual; it may or may not match a particular implementation. Refer to Bach [1986] for a discussion of these structures in System V. McKusick et al. [1996] describe these structures in 4.4BSD. McKusick and Neville-Neil [2005] cover FreeBSD 5.2. For a similar discussion of Solaris, see McDougall and Mauro [2007]. The Linux 2.6 kernel architecture is discussed in Bovet and Cesati [2006].

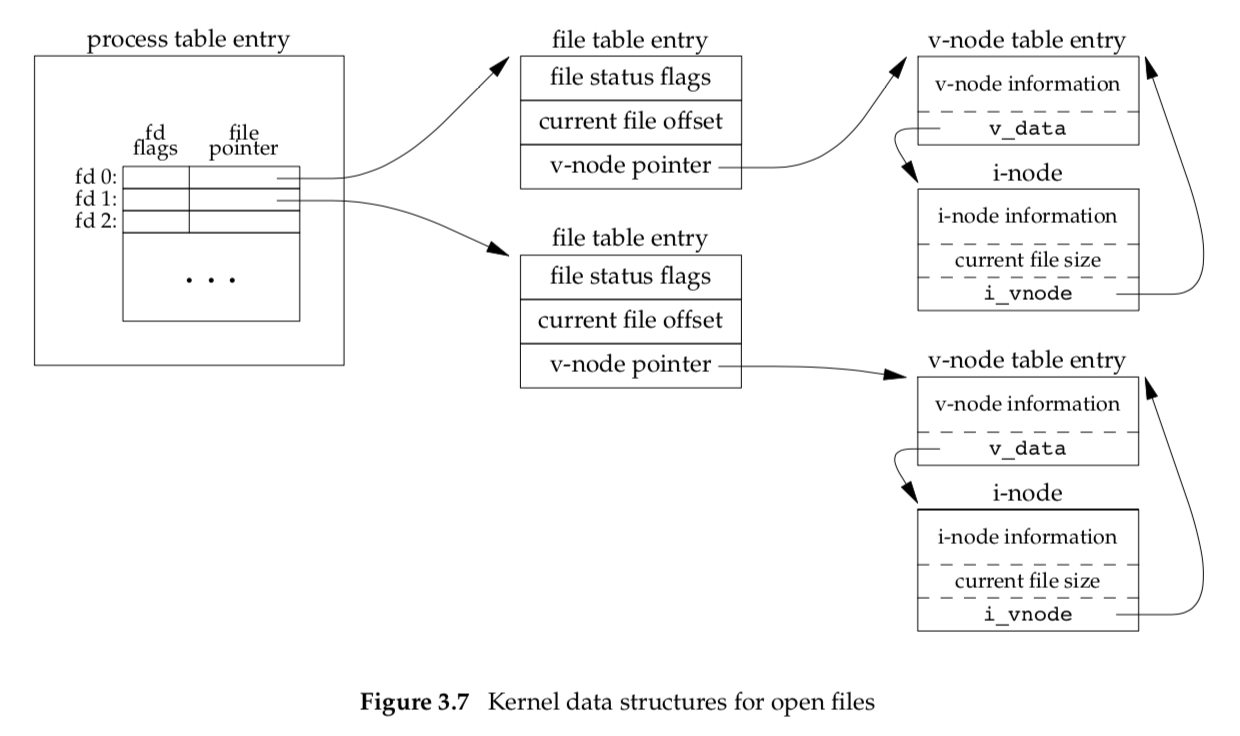

The kernel uses three data structures to represent an open file, and the relationships among them determine the effect one process has on another with regard to file sharing.

Every process has an entry in the process table. Within each process table entry is a table of open file descriptors, which we can think of as a vector, with one entry per descriptor. Associated with each file descriptor are

- The file descriptor flags (close-on-exec; refer to Figure 3.7 and Section 3.14)

- A pointer to a file table entry

The kernel maintains a file table for all open files. Each file table entry contains

- The file status flags for the file, such as read, write, append, sync, and nonblocking; more on these in Section 3.14

- The current file offset

- A pointer to the v-node table entry for the file

Each open file (or device) has a v-node structure that contains information about the type of file and pointers to functions that operate on the file. For most files, the v-node also contains the i-node for the file. This information is read from disk when the file is opened, so that all the pertinent information about the file is readily available. For example, the i-node contains the owner of the file, the size of the file, pointers to where the actual data blocks for the file are located on disk, and so on. (We talk more about i-nodes in Section 4.14 when we describe the typical UNIX file system in more detail.)

Linux has no v-node. Instead, a generic i-node structure is used. Although the implementations differ, the v-node is conceptually the same as a generic i-node. Both point to an i-node structure specific to the file system.

We’re ignoring some implementation details that don’t affect our discussion. For example, the table of open file descriptors can be stored in the user area (a separate per- process structure that can be paged out) instead of the process table. Also, these tables can be implemented in numerous ways—they need not be arrays; one alternate implementation is a linked lists of structures. Regardless of the implementation details, the general concepts remain the same.

Figure 3.7 shows a pictorial arrangement of these three tables for a single process that has two different files open: one file is open on standard input (file descriptor 0), and the other is open on standard output (file descriptor 1).

The arrangement of these three tables has existed since the early versions of the UNIX System [Thompson 1978]. This arrangement is critical to the way files are shared among processes. We’ll return to this figure in later chapters, when we describe additional ways that files are shared.

The v-node was invented to provide support for multiple file system types on a single computer system. This work was done independently by Peter Weinberger (Bell Laboratories) and Bill Joy (Sun Microsystems). Sun called this the Virtual File System and called the file system–independent portion of the i-node the v-node [Kleiman 1986]. The v-node propagated through various vendor implementations as support for Sun’s Network File System (NFS) was added. The first release from Berkeley to provide v-nodes was the 4.3BSD Reno release, when NFS was added.

In SVR4, the v-node replaced the file system–independent i-node of SVR3. Solaris is derived from SVR4 and, therefore, uses v-nodes.

Instead of splitting the data structures into a v-node and an i-node, Linux uses a file system–independent i-node and a file system–dependent i-node.

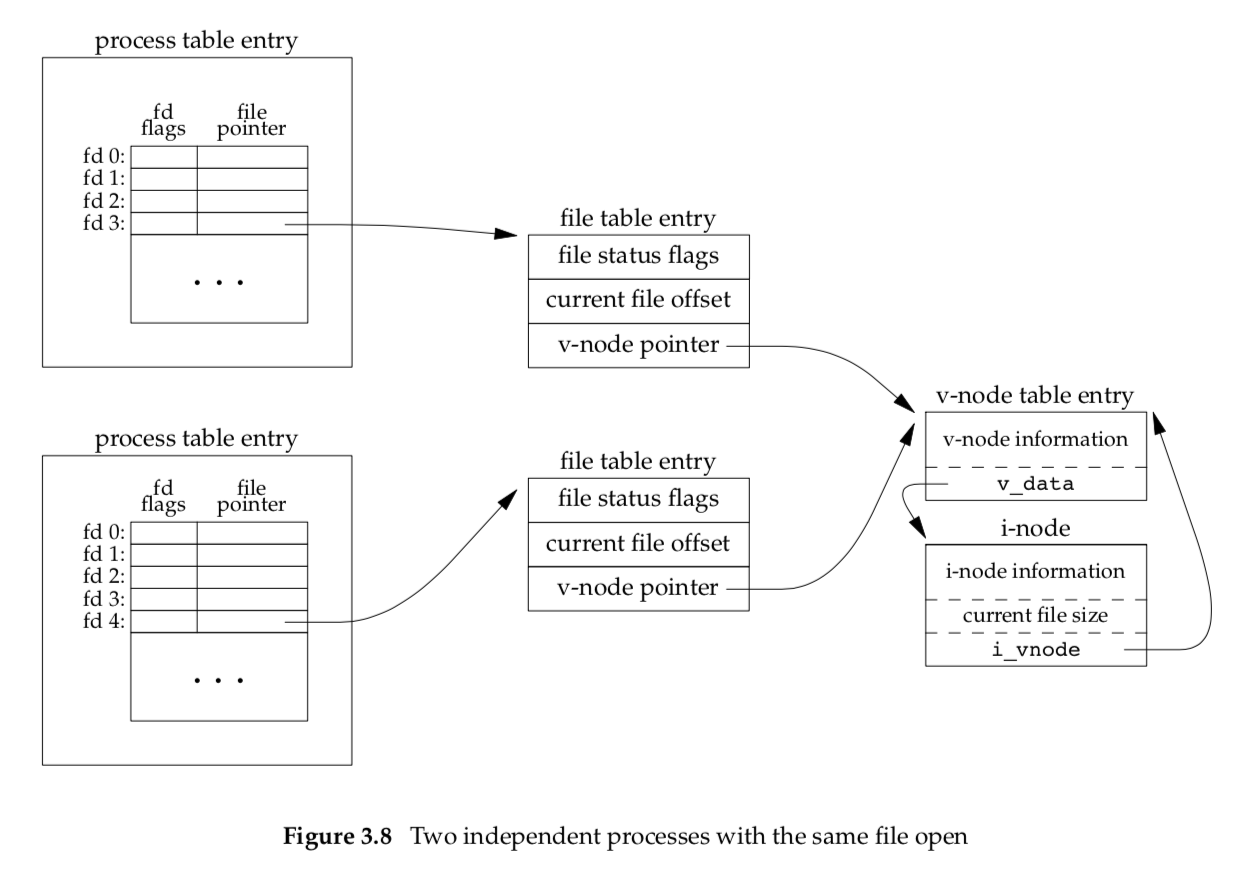

If two independent processes have the same file open, we could have the arrangement shown in Figure 3.8.

We assume here that the first process has the file open on descriptor 3 and that the second process has that same file open on descriptor 4. Each process that opens the file gets its own file table entry, but only a single v-node table entry is required for a given file. One reason each process gets its own file table entry is so that each process has its own current offset for the file.

Given these data structures, we now need to be more specific about what happens with certain operations that we’ve already described.

- After each write is complete, the current file offset in the file table entry is incremented by the number of bytes written. If this causes the current file offset to exceed the current file size, the current file size in the i-node table entry is set to the current file offset (for example, the file is extended).

- If a file is opened with the O_APPEND flag, a corresponding flag is set in the file status flags of the file table entry. Each time a write is performed for a file with this append flag set, the current file offset in the file table entry is first set to the current file size from the i-node table entry. This forces every write to be appended to the current end of file. 如果一个文件打开时使用

O_APPEND标志,相应的标志会设置到文件表项的文件状态符。每次进行写操作时,文件表项就会首先将当前文件偏移量设置为 i 结点表项的当前文件大小。这样就可以强制每次都写到文件末尾了。 - If a file is positioned to its current end of file using lseek, all that happens is the current file offset in the file table entry is set to the current file size from the i-node table entry. (Note that this is not the same as if the file was opened with the O_APPEND flag, as we will see in Section 3.11.)

- The lseek function modifies only the current file offset in the file table entry. No I/O takes place.

It is possible for more than one file descriptor entry to point to the same file table entry, as we’ll see when we discuss the dup function in Section 3.12. This also happens after a fork when the parent and the child share the same file table entry for each open descriptor (Section 8.3).

Note the difference in scope between the file descriptor flags and the file status flags. The former apply only to a single descriptor in a single process, whereas the latter apply to all descriptors in any process that point to the given file table entry. When we describe the fcntl function in Section 3.14, we’ll see how to fetch and modify both the file descriptor flags and the file status flags.

Everything that we’ve described so far in this section works fine for multiple processes that are reading the same file. Each process has its own file table entry with its own current file offset. Unexpected results can arise, however, when multiple processes write to the same file. To see how to avoid some surprises, we need to understand the concept of atomic operations.

Atomic Operations

Appending to a File

Consider a single process that wants to append to the end of a file. Older versions of the UNIX System didn’t support the O_APPEND option to open, so the program was coded as follows:

1 | if (lseek(fd, 0L, 2) < 0) /* position to EOF */ |

This works fine for a single process, but problems arise if multiple processes use this technique to append to the same file. (This scenario can arise if multiple instances of the same program are appending messages to a log file, for example.)

Assume that two independent processes, A and B, are appending to the same file. Each has opened the file but without the O_APPEND flag. This gives us the same picture as Figure 3.8. Each process has its own file table entry, but they share a single v-node table entry. Assume that process A does the lseek and that this sets the current offset for the file for process A to byte offset 1,500 (the current end of file). Then the kernel switches processes, and B continues running. Process B then does the lseek, which sets the current offset for the file for process B to byte offset 1,500 also (the current end of file). Then B calls write, which increments B’s current file offset for the file to 1,600. Because the file’s size has been extended, the kernel also updates the current file size in the v-node to 1,600. Then the kernel switches processes and A resumes. When A calls write, the data is written starting at the current file offset for A, which is byte offset 1,500. This overwrites the data that B wrote to the file.

The problem here is that our logical operation of ‘‘position to the end of file and write’’ requires two separate function calls (as we’ve shown it). The solution is to have the positioning to the current end of file and the write be an atomic operation with regard to other processes. Any operation that requires more than one function call cannot be atomic, as there is always the possibility that the kernel might temporarily suspend the process between the two function calls (as we assumed previously).

The UNIX System provides an atomic way to do this operation if we set the O_APPEND flag when a file is opened. As we described in the previous section, this causes the kernel to position the file to its current end of file before each write. We no longer have to call lseek before each write.

pread and pwrite Functions

The Single UNIX Specification includes two functions that allow applications to seek and perform I/O atomically: pread and pwrite.

1 |

|

Calling pread is equivalent to calling lseek followed by a call to read, with the following exceptions.

- There is no way to interrupt the two operations that occur when we call pread.

- The current file offset is not updated.

Calling pwrite is equivalent to calling lseek followed by a call to write, with similar exceptions.

Creating a File

We saw another example of an atomic operation when we described the O_CREAT and O_EXCL options for the open function. When both of these options are specified, the open will fail if the file already exists. We also said that the check for the existence of the file and the creation of the file was performed as an atomic operation. If we didn’t have this atomic operation, we might try

1 | if ((fd = open(path, O_WRONLY)) < 0) { |

The problem occurs if the file is created by another process between the open and the creat. If the file is created by another process between these two function calls, and if that other process writes something to the file, that data is erased when this creat is executed. Combining the test for existence and the creation into a single atomic operation avoids this problem.

In general, the term atomic operation refers to an operation that might be composed of multiple steps. If the operation is performed atomically, either all the steps are performed (on success) or none are performed (on failure). It must not be possible for only a subset of the steps to be performed. We’ll return to the topic of atomic operations when we describe the link function (Section 4.15) and record locking (Section 14.3).

dup and dup2 Functions

An existing file descriptor is duplicated by either of the following functions:

1 |

|

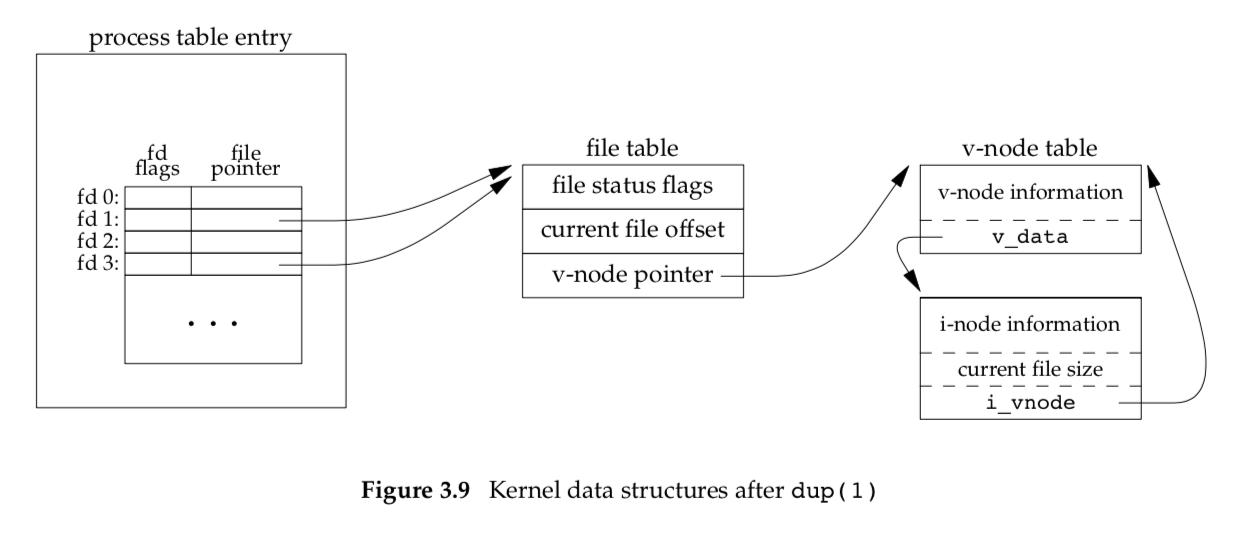

The new file descriptor returned by dup is guaranteed to be the lowest-numbered available file descriptor. With dup2, we specify the value of the new descriptor with the fd2 argument. If fd2 is already open, it is first closed. If fd equals fd2, then dup2 returns fd2 without closing it. Otherwise, the FD_CLOEXEC file descriptor flag is cleared for fd2, so that fd2 is left open if the process calls exec.

The new file descriptor that is returned as the value of the functions shares the same file table entry as the fd argument. We show this in Figure 3.9.

In this figure, we assume that when it’s started, the process executes

1 | newfd = dup(1); |

We assume that the next available descriptor is 3 (which it probably is, since 0, 1, and 2 are opened by the shell). Because both descriptors point to the same file table entry, they share the same file status flags—read, write, append, and so on—and the same current file offset.

Each descriptor has its own set of file descriptor flags. As we describe in Section 3.14, the close-on-exec file descriptor flag for the new descriptor is always cleared by the dup functions.

Another way to duplicate a descriptor is with the fcntl function, which we describe in Section 3.14. Indeed, the call

1 | dup(fd); |

is equivalent to

1 | fcntl(fd, F_DUPFD, 0); |

Similarly, the call

1 | dup2(fd, fd2); |

is equivalent to

1 | close(fd2); |

In this last case, the dup2 is not exactly the same as a close followed by an fcntl. The differences are as follows:

- dup2 is an atomic operation, whereas the alternate form involves two function calls. It is possible in the latter case to have a signal catcher called between the close and the fcntl that could modify the file descriptors. (We describe signals in Chapter 10.) The same problem could occur if a different thread changes the file descriptors. (We describe threads in Chapter 11.)

- There are some errno differences between dup2 and fcntl.

The dup2 system call originated with Version 7 and propagated through the BSD releases. The fcntl method for duplicating file descriptors appeared with System III and continued with SystemV. SVR3.2 picked up the dup2 function, and 4.2BSD picked up the fcntl function and the F_DUPFD functionality. POSIX.1 requires both dup2 and the F_DUPFD feature of fcntl.

sync, fsync, and fdatasync Functions

Traditional implementations of the UNIX System have a buffer cache or page cache in the kernel through which most disk I/O passes. When we write data to a file, the data is normally copied by the kernel into one of its buffers and queued for writing to disk at some later time. This is called delayed write. (Chapter 3 of Bach [1986] discusses this buffer cache in detail.)

The kernel eventually writes all the delayed-write blocks to disk, normally when it needs to reuse the buffer for some other disk block. To ensure consistency of the file system on disk with the contents of the buffer cache, the sync, fsync, and fdatasync functions are provided.

1 |

|

The sync function simply queues all the modified block buffers for writing and returns; it does not wait for the disk writes to take place.

The function sync is normally called periodically (usually every 30 seconds) from a system daemon, often called update. This guarantees regular flushing of the kernel’s block buffers. The command sync(1) also calls the sync function.

The function fsync refers only to a single file, specified by the file descriptor fd, and waits for the disk writes to complete before returning. This function is used when an application, such as a database, needs to be sure that the modified blocks have been written to the disk.

The fdatasync function is similar to fsync, but it affects only the data portions of a file. With fsync, the file’s attributes are also updated synchronously.

All four of the platforms described in this book support sync and fsync. However, FreeBSD 8.0 does not support fdatasync.

fcntl Function

The fcntl function can change the properties of a file that is already open.

1 |

|

In the examples in this section, the third argument is always an integer, corresponding to the comment in the function prototype just shown. When we describe record locking in Section 14.3, however, the third argument becomes a pointer to a structure.

The fcntl function is used for five different purposes.

Duplicate an existing descriptor (cmd = F_DUPFD or F_DUPFD_CLOEXEC)

Get/set file descriptor flags (cmd = F_GETFD or F_SETFD)

Get/set file status flags (cmd = F_GETFL or F_SETFL)

Get/set asynchronous I/O ownership (cmd = F_GETOWN or F_SETOWN)

Get/set record locks (cmd = F_GETLK, F_SETLK, or F_SETLKW)

We’ll now describe the first 8 of these 11 cmd values. (We’ll wait until Section 14.3 to describe the last 3, which deal with record locking.) Refer to Figure 3.7, as we’ll discuss both the file descriptor flags associated with each file descriptor in the process table entry and the file status flags associated with each file table entry.

F_DUPFD Duplicate the file descriptor fd. The new file descriptor is returned as the value of the function. It is the lowest-numbered descriptor that is not already open, and that is greater than or equal to the third argument (taken as an integer). The new descriptor shares the same file table entry as fd. (Refer to Figure 3.9.) But the new descriptor has its own set of file descriptor flags, and its FD_CLOEXEC file descriptor flag is cleared. (This means that the descriptor is left open across an exec, which we discuss in Chapter 8.)

F_DUPFD_CLOEXEC Duplicate the file descriptor and set the FD_CLOEXEC file descriptor flag associated with the new descriptor. Returns the new file descriptor.

F_GETFD Return the file descriptor flags for fd as the value of the function. Currently, only one file descriptor flag is defined: the FD_CLOEXEC flag.

F_SETFD Set the file descriptor flags for fd. The new flag value is set from the third argument (taken as an integer).

Be aware that some existing programs that deal with the file descriptor flags don’t use the constant FD_CLOEXEC. Instead, these programs set the flag to either 0 (don’t close-on-exec, the default) or 1 (do close-on-exec).

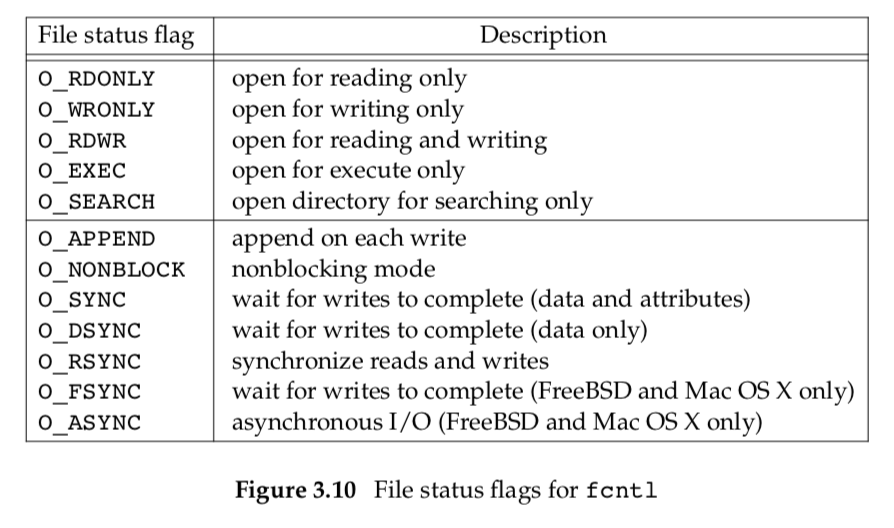

F_GETFL Return the file status flags for fd as the value of the function. We described the file status flags when we described the open function. They are listed in Figure 3.10.

Unfortunately, the five access-mode flags—O_RDONLY, O_WRONLY, O_RDWR, O_EXEC, and O_SEARCH—are not separate bits that can be tested. (As we mentioned earlier, the first three often have the values 0, 1, and 2, respectively, for historical reasons. Also, these five values are mutually exclusive; a file can have only one of them enabled.) Therefore, we must first use the O_ACCMODE mask to obtain the access-mode bits and then compare the result against any of the five values.

F_SETFL Set the file status flags to the value of the third argument (taken as an integer). The only flags that can be changed are O_APPEND, O_NONBLOCK, O_SYNC, O_DSYNC, O_RSYNC, O_FSYNC, and O_ASYNC.

F_GETOWN Get the process ID or process group ID currently receiving the SIGIO and SIGURG signals. We describe these asynchronous I/O signals in Section 14.5.2.

F_SETOWN Set the process ID or process group ID to receive the SIGIO and SIGURG signals. A positive arg specifies a process ID. A negative arg implies a process group ID equal to the absolute value of arg.

The return value from fcntl depends on the command. All commands return −1 on an error or some other value if OK. The following four commands have special return values: F_DUPFD, F_GETFD, F_GETFL, and F_GETOWN. The first command returns the new file descriptor, the next two return the corresponding flags, and the final command returns a positive process ID or a negative process group ID.

Example

The program in Figure 3.11 takes a single command-line argument that specifies a file descriptor and prints a description of selected file flags for that descriptor.

Figure 3.11 Print file flags for specified descriptor

1 |

|

Note that we use the feature test macro _POSIX_C_SOURCE and conditionally compile the file access flags that are not part of POSIX.1. The following script shows the operation of the program, when invoked from bash (the Bourne-again shell). Results will vary, depending on which shell you use.

1 | ➜ apue.3e ./fig3.11 0 < /dev/tty |

The clause 5<>temp.foo opens the file temp.foo for reading and writing on file descriptor 5.

Example

When we modify either the file descriptor flags or the file status flags, we must be careful to fetch the existing flag value, modify it as desired, and then set the new flag value. We can’t simply issue an F_SETFD or an F_SETFL command, as this could turn off flag bits that were previously set.

Figure 3.12 shows a function that sets one or more of the file status flags for a descriptor.

Figure 3.12 Turn on one or more of the file status flags for a descriptor

1 |

|

If we change the middle statement to

1 | val &= ̃flags; /* turn flags off */ |

we have a function named clr_fl, which we’ll use in some later examples. This statement logically ANDs the one’s complement of flags with the current val.

If we add the line

1 | set_fl(STDOUT_FILENO, O_SYNC); |

to the beginning of the program shown in Figure 3.5, we’ll turn on the synchronous- write flag. This causes each write to wait for the data to be written to disk before returning. Normally in the UNIX System, a write only queues the data for writing; the actual disk write operation can take place sometime later. A database system is a likely candidate for using O_SYNC, so that it knows on return from a write that the data is actually on the disk, in case of an abnormal system failure.

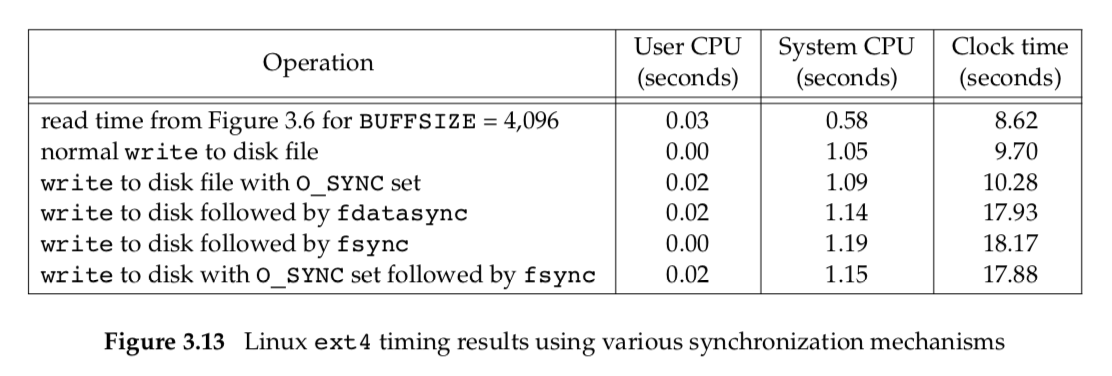

We expect the O_SYNC flag to increase the system and clock times when the program runs. To test this, we can run the program in Figure 3.5, copying 492.6 MB of data from one file on disk to another and compare this with a version that does the same thing with the O_SYNC flag set. The results from a Linux system using the ext4 file system are shown in Figure 3.13.

The six rows in Figure 3.13 were all measured with a BUFFSIZE of 4,096 bytes. The results in Figure 3.6 were measured while reading a disk file and writing to /dev/null, so there was no disk output. The second row in Figure 3.13 corresponds to reading a disk file and writing to another disk file. This is why the first and second rows in Figure 3.13 are different. The system time increases when we write to a disk file, because the kernel now copies the data from our process and queues the data for writing by the disk driver. We expect the clock time to increase as well when we write to a disk file.

When we enable synchronous writes, the system and clock times should increase significantly. As the third row shows, the system time for writing synchronously is not much more expensive than when we used delayed writes. This implies that the Linux operating system is doing the same amount of work for delayed and synchronous writes (which is unlikely), or else the O_SYNC flag isn’t having the desired effect. In this case, the Linux operating system isn’t allowing us to set the O_SYNC flag using fcntl, instead failing without returning an error (but it would have honored the flag if we were able to specify it when the file was opened).

The clock time in the last three rows reflects the extra time needed to wait for all of the writes to be committed to disk. After writing a file synchronously, we expect that a call to fsync will have no effect. This case is supposed to be represented by the last row in Figure 3.13, but since the O_SYNC flag isn’t having the intended effect, the last row behaves the same way as the fifth row.

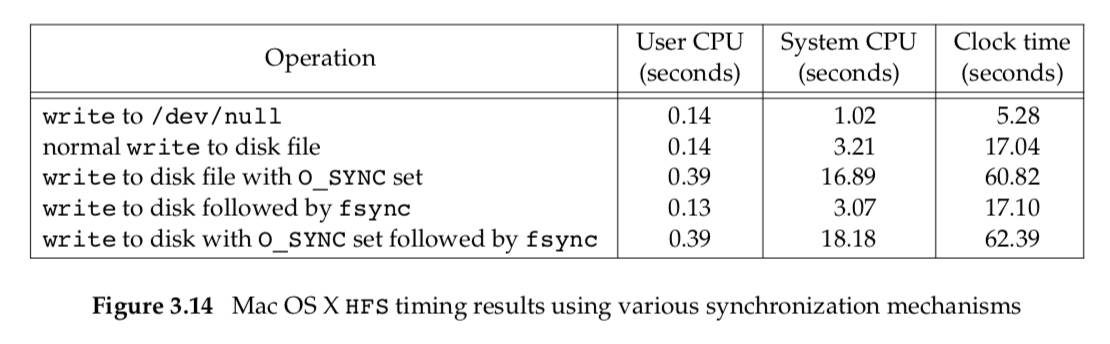

Figure 3.14 shows timing results for the same tests run on Mac OS X 10.6.8, which uses the HFS file system. Note that the times match our expectations: synchronous writes are far more expensive than delayed writes, and using fsync with synchronous writes makes very little difference. Note also that adding a call to fsync at the end of the delayed writes makes little measurable difference. It is likely that the operating system flushed previously written data to disk as we were writing new data to the file, so by the time that we called fsync, very little work was left to be done.

Compare fsync and fdatasync, both of which update a file’s contents when we say so, with the O_SYNC flag, which updates a file’s contents every time we write to the file. The performance of each alternative will depend on many factors, including the underlying operating system implementation, the speed of the disk drive, and the type of the file system.

With this example, we see the need for fcntl. Our program operates on a descriptor (standard output), never knowing the name of the file that was opened on that descriptor. We can’t set the O_SYNC flag when the file is opened, since the shell opened the file. With fcntl, we can modify the properties of a descriptor, knowing only the descriptor for the open file. We’ll see another need for fcntl when we describe nonblocking pipes (Section 15.2), since all we have with a pipe is a descriptor.

ioctl Function

The ioctl function has always been the catchall for I/O operations. Anything that couldn’t be expressed using one of the other functions in this chapter usually ended up being specified with an ioctl. Terminal I/O was the biggest user of this function. (When we get to Chapter 18, we’ll see that POSIX.1 has replaced the terminal I/O operations with separate functions.)

1 |

|

The ioctl function was included in the Single UNIX Specification only as an extension for dealing with STREAMS devices [Rago 1993], but it was moved to obsolescent status in SUSv4. UNIX System implementations use ioctl for many miscellaneous device operations. Some implementations have even extended it for use with regular files.

The prototype that we show corresponds to POSIX.1. FreeBSD 8.0 and Mac OS X 10.6.8 declare the second argument as an unsigned long. This detail doesn’t matter, since the second argument is always a #defined name from a header.

For the ISO C prototype, an ellipsis is used for the remaining arguments. Normally, however, there is only one more argument, and it’s usually a pointer to a variable or a structure.

In this prototype, we show only the headers required for the function itself. Normally, additional device-specific headers are required. For example, the ioctl commands for terminal I/O, beyond the basic operations specified by POSIX.1, all require the <termios.h> header.

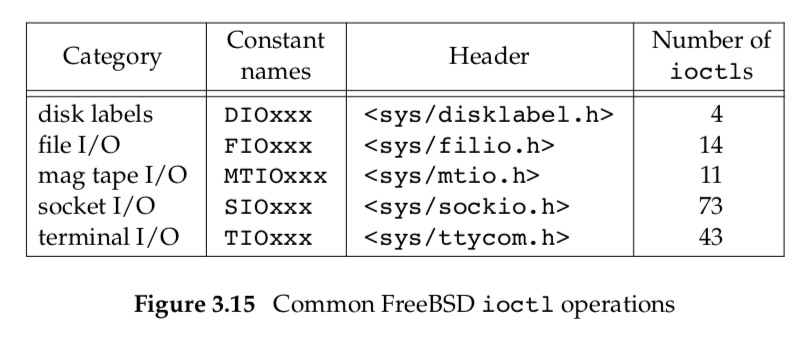

Each device driver can define its own set of ioctl commands. The system, however, provides generic ioctl commands for different classes of devices. Examples of some of the categories for these generic ioctl commands supported in FreeBSD are summarized in Figure 3.15.

The mag tape operations allow us to write end-of-file marks on a tape, rewind a tape, space forward over a specified number of files or records, and the like. None of these operations is easily expressed in terms of the other functions in the chapter (read, write, lseek, and so on), so the easiest way to handle these devices has always been to access their operations using ioctl.

We use the ioctl function in Section 18.12 to fetch and set the size of a terminal’s window, and in Section 19.7 when we access the advanced features of pseudo terminals.

/dev/fd

Newer systems provide a directory named /dev/fd whose entries are files named 0, 1, 2, and so on. Opening the file /dev/fd/n is equivalent to duplicating descriptor n, assuming that descriptor n is open.

The /dev/fd feature was developed by Tom Duff and appeared in the 8th Edition of the Research UNIX System. It is supported by all of the systems described in this book: FreeBSD 8.0, Linux 3.2.0, Mac OS X 10.6.8, and Solaris 10. It is not part of POSIX.1.

In the function call

1 | fd = open("/dev/fd/0", mode); |

most systems ignore the specified mode, whereas others require that it be a subset of the mode used when the referenced file (standard input, in this case) was originally opened. Because the previous open is equivalent to

1 | fd = dup(0); |

the descriptors 0 and fd share the same file table entry (Figure 3.9). For example, if descriptor 0 was opened read-only, we can only read on fd. Even if the system ignores the open mode and the call

1 | fd = open("/dev/fd/0", O_RDWR); |

succeeds, we still can’t write to fd.

The Linux implementation of /dev/fd is an exception. It maps file descriptors into symbolic links pointing to the underlying physical files. When you open /dev/fd/0, for example, you are really opening the file associated with your standard input. Thus the mode of the new file descriptor returned is unrelated to the mode of the /dev/fd file descriptor.

We can also call creat with a /dev/fd pathname argument as well as specify O_CREAT in a call to open. This allows a program that calls creat to still work if the pathname argument is /dev/fd/1, for example.

Beware of doing this on Linux. Because the Linux implementation uses symbolic links to the real files, using creat on a /dev/fd file will result in the underlying file being truncated.

Some systems provide the pathnames /dev/stdin, /dev/stdout, and /dev/stderr. These pathnames are equivalent to /dev/fd/0, /dev/fd/1, and /dev/fd/2, respectively.

The main use of the /dev/fd files is from the shell. It allows programs that use pathname arguments to handle standard input and standard output in the same manner as other pathnames. For example, the cat(1) program specifically looks for an input filename of - and uses it to mean standard input. The command

1 | filter file2 | cat file1 - file3 | lpr |

is an example. First, cat reads file1, then its standard input (the output of the filter program on file2), and then file3. If /dev/fd is supported, the special handling of - can be removed from cat, and we can enter

1 | filter file2 | cat file1 /dev/fd/0 file3 | lpr |

The special meaning of - as a command-line argument to refer to the standard input or the standard output is a kludge that has crept into many programs. There are also problems if we specify - as the first file, as it looks like the start of another command-line option. Using /dev/fd is a step toward uniformity and cleanliness.

Summary

This chapter has described the basic I/O functions provided by the UNIX System. These are often called the unbuffered I/O functions because each read or write invokes a system call into the kernel. Using only read and write, we looked at the effect of various I/O sizes on the amount of time required to read a file. We also looked at several ways to flush written data to disk and their effect on application performance.

Atomic operations were introduced when multiple processes append to the same file and when multiple processes create the same file. We also looked at the data structures used by the kernel to share information about open files. We’ll return to these data structures later in the text.

We also described the ioctl and fcntl functions. We return to both of these functions later in the book. In Chapter 14, we’ll use fcntl for record locking. In Chapter 18 and Chapter 19, we’ll use ioctl when we deal with terminal devices.

Exercises

When reading or writing a disk file, are the functions described in this chapter really unbuffered? Explain.

Write your own dup2 function that behaves the same way as the dup2 function described in Section 3.12, without calling the fcntl function. Be sure to handle errors correctly.

Assume that a process executes the following three function calls:

1

2

3fd1 = open(path, oflags);

fd2 = dup(fd1);

fd3 = open(path, oflags);Draw the resulting picture, similar to Figure 3.9. Which descriptors are affected by an fcntl on fd1 with a command of F_SETFD? Which descriptors are affected by an fcntl on fd1 with a command of F_SETFL?

The following sequence of code has been observed in various programs:

1

2

3

4dup2(fd, 0);

dup2(fd, 1);

dup2(fd, 2);

if (fd > 2)

close(fd);

To see why the if test is needed, assume that fd is 1 and draw a picture of what happens to the three descriptor entries and the corresponding file table entry with each call to dup2. Then assume that fd is 3 and draw the same picture.